Conservation Areas. Part 2. Understanding The Framework

- Davide di Martino

- Jan 19

- 6 min read

How this article works

This is the practical companion to Part 1. If that earlier essay explored why conservation areas exist and how they came to shape London’s identity, this one explains what they mean for daily life — what can and cannot be changed, and how those decisions are made.

You can read it straight through as an introduction to the system, or skip ahead to the most useful sections: Appraisals and Management Plans and Article 4 Directions. These two tools are the real engines of conservation policy. Appraisals describe why an area is special and outline which alterations are likely to harm its character — often roofs, front façades and anything visible from the street. Article 4 Directions, meanwhile, limit automatic planning permissions, especially for works such as window replacements, boundary walls, paving, and roof extensions.

If you live or work in a conservation area, understanding these documents will save time, money and frustration — and, more importantly, deepen your appreciation of what makes your neighbourhood distinct.

Living with heritage

Conservation areas sit at the meeting point of architecture, law and identity. Their purpose is not to prevent change but to guide it, ensuring that the city continues to evolve without losing its memory. Knowing the framework helps you navigate it, but it also helps you enjoy what it protects: the balance of your street, the grain of brick, the canopy of trees that makes the air gentler.

1 The legal foundation

The authority for conservation areas lies in Section 69 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. Every local council must identify parts of its district that are of special architectural or historic interest, whose character or appearance it is desirable to preserve or enhance.

That phrase — preserve or enhance — still defines how planners assess proposals. It is less about freezing time than about allowing change that sustains significance.

Historic England summarises it well: conservation is the management of change in a way that sustains significance. The city continues to move, but with care.

2 Different kinds of conservation area

The term covers a wide range of contexts. Each type brings its own sensitivities and opportunities.

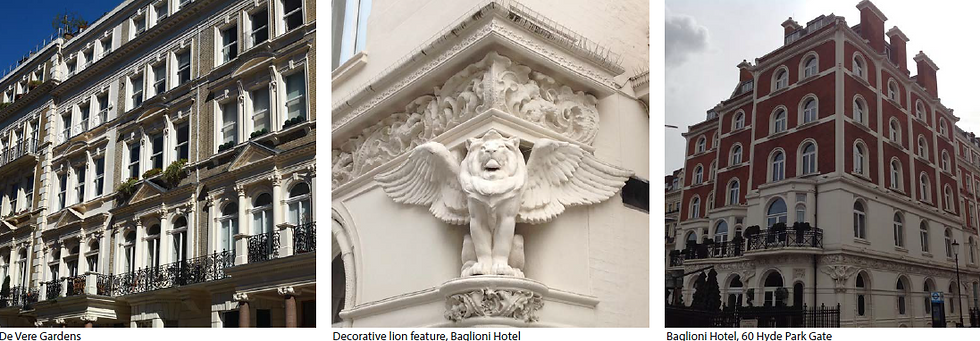

Architectural or historic character areas

These form the majority of London’s designations: Georgian terraces in Islington, late-Victorian streets in Hackney, Edwardian villas in Ealing. Their value lies in the harmony of façades, materials and rooflines. Altering a window or boundary wall can affect an entire rhythm.

Our new Bromley project, for example, sits in one such area, where the designation recognises the consistent relationship between plots, rather than any single building.

Garden suburb and green character areas

Neighbourhoods such as Hampstead Garden Suburb blend architecture with landscape planning. Hedges, trees and verges are part of the composition. Removing a tree or paving a garden can alter character as much as a new extension.

Mixed or industrial heritage areas

In Camden’s workshops or the Docklands, the essence lies in the grain of yards and warehouses. Scale and spatial rhythm matter more than ornament.

Landscape or topographical areas

Along riverbanks or on rising ground, conservation may focus on skyline, contour and view. Control extends to massing, planting and how buildings meet the land.

3 Layers of protection

Most conservation areas overlap with other designations. Understanding the layers prevents confusion.

Listed buildings

A listed building is protected nationally for its special interest. Grades I, II* and II mark levels of importance. Any alteration affecting its character requires separate Listed Building Consent. Within a conservation area, this protection extends to the building’s setting — the surrounding streets and spaces.

Locally listed and non-designated heritage assets

Councils often maintain local heritage lists of buildings valued by residents. They appear in appraisals as positive contributors and are material considerations in planning decisions. Altering or demolishing them requires clear justification.

4 Permitted development and Article 4 Directions

The General Permitted Development Order allows some small-scale works without full permission. In conservation areas those rights are narrower, and a council can withdraw them entirely through an Article 4 Direction.

What an Article 4 Direction does

It removes specific permitted-development rights so that changes are assessed individually. It does not forbid work; it requires a proper application. Typical restrictions concern:

Windows, doors and roof coverings

Porches or side extensions

Boundary walls, fences and gates

Roof extensions or dormers

Hard-surfacing of front gardens

Painting or rendering façades visible from public streets

Boroughs such as Camden, Islington, Hackney, Kensington & Chelsea and Richmond maintain detailed Article 4 maps showing where these controls apply.

How it is applied

A direction must be justified, consulted upon and confirmed by the local authority. Its reasoning almost always refers to the Conservation Area Appraisal, which identifies particular vulnerabilities — often the gradual loss of traditional details.

What it means for design

In an Article 4 area, even like-for-like replacements may need permission. Expect to provide measured drawings, material samples and a design statement showing how your proposal preserves or enhances the area’s character.

5 Conservation Area Appraisals and Management Plans

If the Act provides authority, the appraisal provides understanding. It explains why the area is special and how it should be managed.

What an appraisal contains

A typical appraisal describes:

Historical development and urban form

Architectural types and materials

Street patterns, open spaces, trees and key views

Buildings that contribute positively, neutrally or negatively

Pressures and opportunities for change

Appraisals often specify the kinds of intervention regarded as harmful: changes to roof profiles, loss of chimneys, modernised windows or alterations visible from the street. They act as both evidence and guide. Historic England recommends updating them every five years.

Management Plans

Many councils pair the appraisal with a Management Plan setting out maintenance policies, public-realm priorities and guidance on sustainability. Together, they form the local design manual.

Why they matter

Planners consult the appraisal first when assessing proposals. A project that undermines the qualities identified as essential is likely to be refused. The appraisal also provides the evidence base for any Article 4 Direction.

6 How planners think

When a proposal arrives, officers consider:

Does it preserve or enhance the character described in the appraisal?

Is its scale and materiality sympathetic to context?

Are details such as joinery and reveals handled with care?

Does it respect key views, trees and open space?

Is new work distinct yet harmonious?

What is the cumulative impact?

If harm is unavoidable, is there clear public benefit?

Are sustainability measures integrated sensitively?

Approvals often carry conditions requiring samples or detailed drawings before work starts.

7 Reading your site

Before design begins, three sources tell you almost everything you need to know.

Article 4 Direction — what needs consent

Check the council’s heritage map or register. If your street is covered, assume that visible external works require permission.

Conservation Area Appraisal — why it matters

Read the sections on character, materials and trees. They reveal what the planning officer will defend most strongly.

Local Guidelines and SPDs — how to treat it

Supplementary Planning Documents translate the appraisal into practice, covering roof extensions, windows, boundaries and retrofits.

Together they create a simple hierarchy:

Appraisal – defines significance

SPD – interprets it

Article 4 – controls consent

8 A short checklist

Before embarking on any work in a conservation area:

Confirm the boundary and any Article 4 Direction.

Read the latest appraisal and management plan.

Check for listed or locally listed status.

Consult SPDs and Local Plan heritage policies.

Survey the street — materials, boundaries, roofline, trees.

Review recent planning approvals.

Engage the conservation officer early.

This preparation ensures that your design speaks the same language as local policy.

9 From bureaucracy to craft

These documents are often seen as bureaucracy, but they are really guides to good design. An appraisal explains what gives a place its strength; SPDs show how to work with it; Article 4 Directions remind us that small details matter.

Working within such a structure encourages precision. Every parapet, window reveal or garden wall contributes to the collective beauty of the street. Conservation work, at any scale, is a quiet craft that rewards attentiveness.

10 Take a moment

Living in a conservation area is a privilege. Before opening the drawings folder, walk your street. Notice how the roofs step with the slope, how the brick catches light, how a line of trees ties the whole together. These are the things the framework protects. It exists so that you, and those after you, can enjoy them — and add to them thoughtfully.

Further reading

Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990, ss. 69–74 — legislation.gov.uk

Historic England, Conservation Area Designation, Appraisal and Management (2019)

General Permitted Development Order (England) (2023)

Local SPDs and CAAs — Camden, Islington, Hackney, Kensington & Chelsea, Richmond

Comments